- ISC2 Community

- :

- Discussions

- :

- Industry News

- :

- Re: OK, *now* we're in trouble ...

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark Topic as New

- Mark Topic as Read

- Float this Topic for Current User

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Printer Friendly Page

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

OK, *now* we're in trouble ...

For some reason, on the Johns Hopkins CoVID-19 dashboard, Canada, as a country, has disappeared. (If you switch to the province/state/dependency mode, the individual provinces with infections still show up.)

This is disturbing, for someone who lives there ...

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

The latest news in the zombie hurricane, killer hornet, "pumpkin spice" KD front: the covida wasp ...

(Despite the name, it's actually not that dangerous ...)

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

OK, down there in the Unexplored Southern Area, you guys are having an election in the midst of a pandemic, and everyone is paying attention.

Up here on the Wet Coast, we are also having an election. Yes, in the midst of a pandemic.

Yes, we have some political scandals. One (female) incumbent has made sexualized remarks about another (female) incumbent, and the leader of the "We Are Trying To Pretend We Aren't Right Wing" party has spent three days not saying anything about it.

But we don't have political parties setting up "official" ballot drop boxes. We don't have concerted efforts to make it more difficult to vote. (Although I suppose anyone can have accidents.) I don't expect our televised debate tonight will be any better than yours, although it could hardly be any worse. I'm taking our ballots over to the district electoral office to drop them off this afternoon, before the debate, because I don't want anyone, in the midst of a pandemic, to mess with our health minister or chief public health officer, the party in power is doing a decent job, and the leader of the "We Are Trying ..." party has all the charisma of a turnip. (Sorry, Sonia, but in the middle of a disaster I just don't feel like trying something untested.)

I'm sorry if this sounds harsh, but I'm just so thankful I'm here and not there.

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

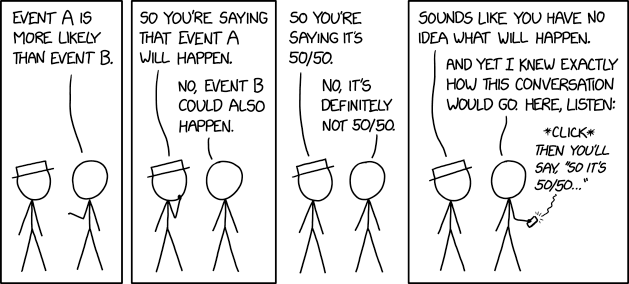

Trying to explain risks to most people tends to end up this way ...

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

@rslade wrote:...

Trying to explain risks to most people tends to end up this way ...

Many years ago I saw a YouTube video of a high school math teacher explaining the colored marble draw probability from a large jar. The jar had X white marbles and X+(a bunch) red marbles; the total marbles in the jar was 2X+(a bunch). The teacher stood in front of his class and carefully explained that the probability of picking either a red or a white marble was 0.5 (50/50) because there were two choices, and 1.0 /2 = 0.5.

SHEEEESH!

Craig

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

Learned helplessness, depression, and poor pandemic processing

A few days ago, in a news report about some aspect of the pandemic, someone used the phrase "learned helplessness." I immediately flashed back to a paper I wrote in university, and a number of problematic aspects of the current CoVID crisis came into much clearer focus.

Learned helplessness is the theory, posited by Martin Seligman and others, that "teaching" subjects that they are helpless; that nothing the subject can do will change their current situation; produces a condition which is indistinguishable from depression. Seligman is not without his critics: I vividly recall one such who wrote that Seligman's experiments were invalid because the brain chemistry of "learned helplessness" subjects was the same as that of depressives, which I felt probably proved Seligman's central thesis.

The learned helplessness theory was experimentally tested in a variety of ways, with both human and animal subjects. One rather intriguing experiment found that punishment was not necessary to create learned helplessness and depression. Random rewards, independent of any action on the part of the subject, could also produce depression, and this factor might explain the high rates of suicide (and the slow suicide by drug use, alcohol, and similar poor life choices) among celebrities and socialites. Random reward in other experiments has demonstrated "superstitious learning," and may relate to some of the weird theories about the CoVID-19 pandemic that have sprung up. But perhaps I am getting ahead of myself.

I have suffered from depression for over half a century. It was probably what sparked my interest in learned helplessness in the first place. I have studied it both from the inside and the outside, and there are a number of aspects and factors that are likely beneficial in our consideration of the current pandemic and crisis. We are faced with a situation where a large number of people, some for the first time in their lives, have learned that they are helpless. It is affecting how they face the disaster, and it has implications for presenting solutions. This has implications not only for the current pandemic, and disasters in general, but for a number of situations in security.

In "Cybersecurity Lessons from CoVID-19" I did briefly discuss the fact that uncertainty makes people less likely to try new solutions. This is a very strong characteristic of depression, and of learned helplessness. Depression has a very strong, and highly negative, impact on learning itself. Depression makes you feel tired, it interferes with focus, it makes your thinking feel sluggish. All of these factors, of course, mean it is difficult to formulate new thoughts or new courses of action to try. But, even if a new action is presented by someone else, "learned helplessness" strongly suggests (to the subject or patient) that, whatever the new idea is, it won't work.

We have seen this in regard to the "rules" of preventing infection, and the unwillingness, in many parts of the population, to follow them. "Wash your hands." Oh, it can't be that simple! (Well, it isn't that simple, but it is easy, and a good first step.) "Avoid groups." Oh, I need an exact number of people to define as a group! (Well, the more people the riskier. And, if that is too hard for you to figure out, 42.) "Wear masks." Oh, there are all kinds of reasons why masks don't work! (Well, masks aren't perfect. But if you won't avoid groups, at least wear a mask.) And, it is quite true, the fact that none of these "rules" guarantees perfect protection makes for uncertainty, and less willingness for people to try (and stick to) any of them. We also need to explain layered defence and defence in depth, and the situations in which each rule is most important, and all of these extra pieces of information add extra uncertainty, and ...

(We, in security, do see this over and over again. Security is poorly understood, and people are uncertain about it, so, even when we present the threat, and the countermeasure to take, people, and employees, and managers, and whole enterprises, often do the very worst thing they can in the situation: nothing.)

One of the central results that came out of the learned helplessness experiments was that one of the primary ways to reduce learned helplessness in subjects was to "force" the subject to succeed. That is, to force the subject, sometimes physically, to take an action that would avoid a punishment or obtain a reward.

This is fairly easy to do with a rat or a dog, more problematic with human subjects, and much, much more difficult to get right when you are dealing with a large population in a democracy in the middle of a pandemic. (Autocratic governments probably have a much easier time of it.) But one way to work towards it is to get people to do something; pretty much *anything*. This is why I included, in the introduction to the book, my advice to Martin about whether retired doctors should go back into front line medicine. I suggested a number of alternative actions that did something helpful, but didn't involve direct exposure to potentially infected patients. (I followed it up with another article directed at those who might not have access to a lot of medical supplies. That article wasn't the best thing I ever wrote, and it didn't make it into the book, but at least I was doing something.)

(In terms of "forcing" people to succeed, I reiterate my admiration for the position of Dr. Bonnie Henry. Attacking people just makes them fixate. [This is also something learned helplessness theory supports.] Be kind, educate, provide guidelines, and support people in getting through their normal activities. Remember social engineering: you catch more flies [or murder hornets] with honey than with vinegar.)

Following any natural or manmade disaster, the news crews roll in and start filming crowds of victims who are just sitting around. They have learned that they are helpless. They certainly look depressed. Some of them do just lie down and die. But, in most cases, shortly something else starts happening. People start to do something, even if it is just to start gathering debris into piles. They are succeeding, even if only at clearing garbage from a small area. Then they start succeeding at salvaging. And, successively, at rebuilding and starting over.

People are finding ways to live with the pandemic. Meetings have to be done differently. Parties have to be done differently. Entertainment has to be done differently. Some of these new ways are remarkably silly. But, unless they are actually dangerous, it is probably best to celebrate and support these bits of the "new normal" in any way we can, any time we can. Any "success" should be supported, because it will lead to other successes, and those other successes may be more important.

Let's go back to random rewards and superstitious learning. When faced with a situation where there is no correlation between the subject's actions and a reward, subjects often seem to "learn" a correlation that doesn't exist. (This false learning may be abetted by the learning and cognitive impairment from depression and learned helplessness that we discussed earlier.) We see this in animal behavioural trials, and also in situations like professional sports and entertainment (with all kinds of "lucky" clothing, totems, and rituals), and now in pandemic "cures." Hydroxychloroquine and oleandrin have been touted as cures on the basis of evidence so flimsy it is almost non-existent. Remdesivir seems to be seen as a miracle cure, even though the studies that have shown it to reduce hospital stays and mortality have demonstrated a limited improvement at best, and the largest recent study showed no significant difference at all. I'm pretty sure ayurvedic cures have no benefit, and gargling with bleach is just flat out dangerous, but all of these have their devotees.

Trying to address superstitious beliefs about CoVID-19 cures will likely be even more problematic. The theory of learned helplessness would seem to indicate that we need to force people into correct thinking, but the truism that "a man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still" is very old, and very, very strong. About all we can do here is to fall back on what security awareness training demonstrates over and over again: repetition, repetition, repetition. Keep driving the truth. Eventually it will get home. (This is borne out by the Spanish Flu pandemic. In 1919 there were the same anti-mask protests that we are seeing today. Eventually they just died out.) (This may have been because anti-maskers died out, but I doubt Darwin works that fast ...)

Decades of experience with depression seem to indicate that depressives should take as a motto the meme that "if you are going through heck [drat you, pr0n filter], keep going." Learned helplessness theory teaches the same thing. Keep moving, keep doing something, keep on. It is a lesson for all of us in the midst of a disaster. It is particularly a lesson for those newly "helpless." But it is also, very strongly, a lesson for those of us who are working in the face of trials, delays, setbacks, surges, second waves, and mounting case and death counts. And it is definitely a rallying cry for those of us fighting the integrity battle against the misinformation and disinformation that is so widely promulgated during this pandemic.

Now, go and do something successful. Even if it’s only washing your hands.

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

Nice post there Rob.

I recall the early 1980s recession, when many of my school friends took the view that there was little point in education, because no matter the paper result, it wouldn't get them into a decent career. I took the view it was better to put in the work anyway. Later as we were working dead end jobs (recessions are great aren't they) we took to racing each other on our cycles on the way into and back from work for something to do, later running and playing football after work. It all seem pretty pointless at the time, until one of us decided he'd try to join the services and needed to get through the medical and basic training. It provided a focus and a way out of the situation.

Steve Wilme CISSP-ISSAP, ISSMP MCIIS

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

OK, so far I've been lucky. Well, the first hotspot was near me, and, as of March 22nd, 50% of the deaths in Canada, and 90% of the deaths in BC were within three blocks of me. And the first three hotspots were all old folks homes that Gloria and I had contacts with. So maybe I'm a dangerous guy to know. Also, Mom's old folks home had an outbreak, but she survived that.

However, now I've learned that two of my grandchildren have CoVID. So far they only have mild symptoms (mostly fatigue), but they are isolating at their Mum's house, and we're pretty worried for them and her.

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

Prayers are with you and the grandkids.

These are spooky times, as Rob said earlier in this string, BE KIND.

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

> Prayers are with you and the grandkids.

Thank you. Appreciate it/them.

====================== (quote inserted randomly by Pegasus Mailer)

rslade@gmail.com rmslade@outlook.com rslade@computercrime.org

It is the greatest of all mistakes to do nothing because you can

only do a little. Do what you can. - Sydney Smith (1771 - 1845)

victoria.tc.ca/techrev/rms.htm http://twitter.com/rslade

http://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/author/p1/

https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Permalink

- Report Inappropriate Content

So, you can now get a home CoVID-19 test kit. At Costco. But there's a few catches.

It costs U$129, or $139 for the fancy version (with video). I assume that allows you to test one person. That's at Costco. You can apparently get it at a pharmacy for $149, or direct from the manufacturer (AZOVA) at the low, low price of only $168.

You have to register with AZOVA before you use the kit. (Actually, you can probably use it, if you buy it at Costco, but you can't get it tested unless you register it, so if you don't register first, you may have wasted $139.) If you buy it from AZOVA, they ship it to you. So that takes 1-3 days.

Then you have to ship it back to AZOVA. How long that takes depends upon how much you are willing to pay to ship it. Then they test it. That takes two or three days. They'll send you a text/SMS or email with a link to get your results. So if you buy it at Costco and ship it via Fedex Urgent, you can probably get results back in five (working) days.

It has been tested, and is accurate. According to AZOVA, who did the testing themselves.

............

Other posts: https://community.isc2.org/t5/forums/recentpostspage/user-id/1324864413

This message may or may not be governed by the terms of

http://www.noticebored.com/html/cisspforumfaq.html#Friday or

https://blogs.securiteam.com/index.php/archives/1468